Why long-distance running doesn't promote longevity 😬

Misconception of fitness activities promoting true health in the long run

This is a tough one as steady-state running has been sky-rocketing among the general public over the last few years, to the point where it now gets more and more difficult to secure a place for a marathon. Meanwhile, ultra-distance events such as Ironman or La Diagonale des Fous (100mi distance & 30k feet elevation) have never been so popular as they are today.

Despite people are training very hard and accomplishing stunning performances, these long-distance running activities are unfortunately detrimental from a health perspective, and I’ll explain why from my longevity lenses.

People who run very legitimately feel good when they do so; their cardio-vascular and lymphatic systems are stimulated, they physiologically trigger beneficial chemicals, and they can even free their minds or listen to podcasts at the same time — no doubt. From a fitness standpoint, this is all good. However, from a health perspective, it is more complex than just moving the body on a terrain and increasing your V̇O₂Max to put it simply — and when it comes to longevity, we need to keep an even broader holistic view.

But, are fitness and health truly intertwined?

The word health is so commonly used by our societies than we have even forgotten what it truly means. Lately, I came across the interesting book Body by Science by Doug McGuff M.D. and John Little, and I very much liked their definitions of fitness, exercice and health as per below, after they thoroughly examined the fitness and medical worlds.

What is fitness?

The bodily state of being physiologically capable of handling challenges that exist above a resting threshold of activity.

Which means, in our case, that running a 10k or 20k+ distance is putting us in that fitness sweet spot.

What is health?

A physiological state in which there is an absence of disease or pathology and that maintains the necessary biologic balance between the catabolic and anabolic states.

Indeed, our body is always in a dynamic state, trying to find equilibrium and homeostasis across its different systems (pH, blood gases, hormone and fluid levels, electrolytes, etc.). This ever-evolving balanced condition between the building-up (anabolic) and breaking-down (catabolic) processes within our body is what truly makes us disease-free from a biological standpoint.

What is exercise?

A specific activity that stimulates a positive physiological adaptation that serves to enhance fitness and health and does not undermine the latter in the process of enhancing the former.

So what’s the issue?

Injuries

Prolonged and repetitive activities such as running long distances over time very often end up causing injuries, generally after a period of 15 to 20 years of performing them. In fact, most of my friends and people I meet over 30 who are still running or used to run have injured their knees, ankles or feet. This pattern always shocked me as evidence that something was wrong. I remember myself in the early days, performing the Cooper test at the gym, trying to run as much as I could in 12 minutes and get a good score; after just training consistently for a few weeks, my right knee started to hurt because of the repetitive movement and impact, forcing me to stop doing this exercise. You might be surprised that several studies show that injury incidence rates consistently ranges from 50% to 60% among runners, with one injury per 60-280 hours of running, depending on runner experience 😨1234567

Catabolism & Inflammation

Muscle protein breakdown, particularly during long runs, and even worse for marathon runners with elevated markers of muscle damage days post-race. Male endurance athletes who train at high volumes frequently experience decreased testosterone levels, shifting their anabolic-catabolic balance toward catabolism.891011

Long-distance runners have chronically elevated inflammatory markers, while inflammatory protein increase in proportion to running distance and duration.1213

Dosing frequency

The key lies is in the dose-response relationship of exercise. If you aim to balance your health — meaning 50% of muscle breakdown caused by its stimuli (catabolic) and 50% of muscle growth thanks to its recovery phase (anabolic) — then you must consider the intensity of your exercise against its volume and frequency, as illustrated below.

How balanced intensity-recovery strengthens

The misconception of fitness promoting health also lies in the belief that some key markers such as a good RHR (Resting Heart Rate) or V̇O₂Max are enough, without considering the continuous metabolic imbalance and latent damage done to joints and articulations. Indeed, many elite athletes have impressive vital statistics yet suffer from chronic inflammation, insufficient recovery, mental burnout and deteriorating joint health. The world of performance inspires through extraordinary stories but it rarely align with long-term health. After all, Blue Zones where people live to 100 aren’t known for emphasizing athletic performance.

Also bear in mind the fitness industry is a $100+ billion business, and there are economical forces that justify selling false or biased beliefs and spreading them through ads, marketing and influencers 😉

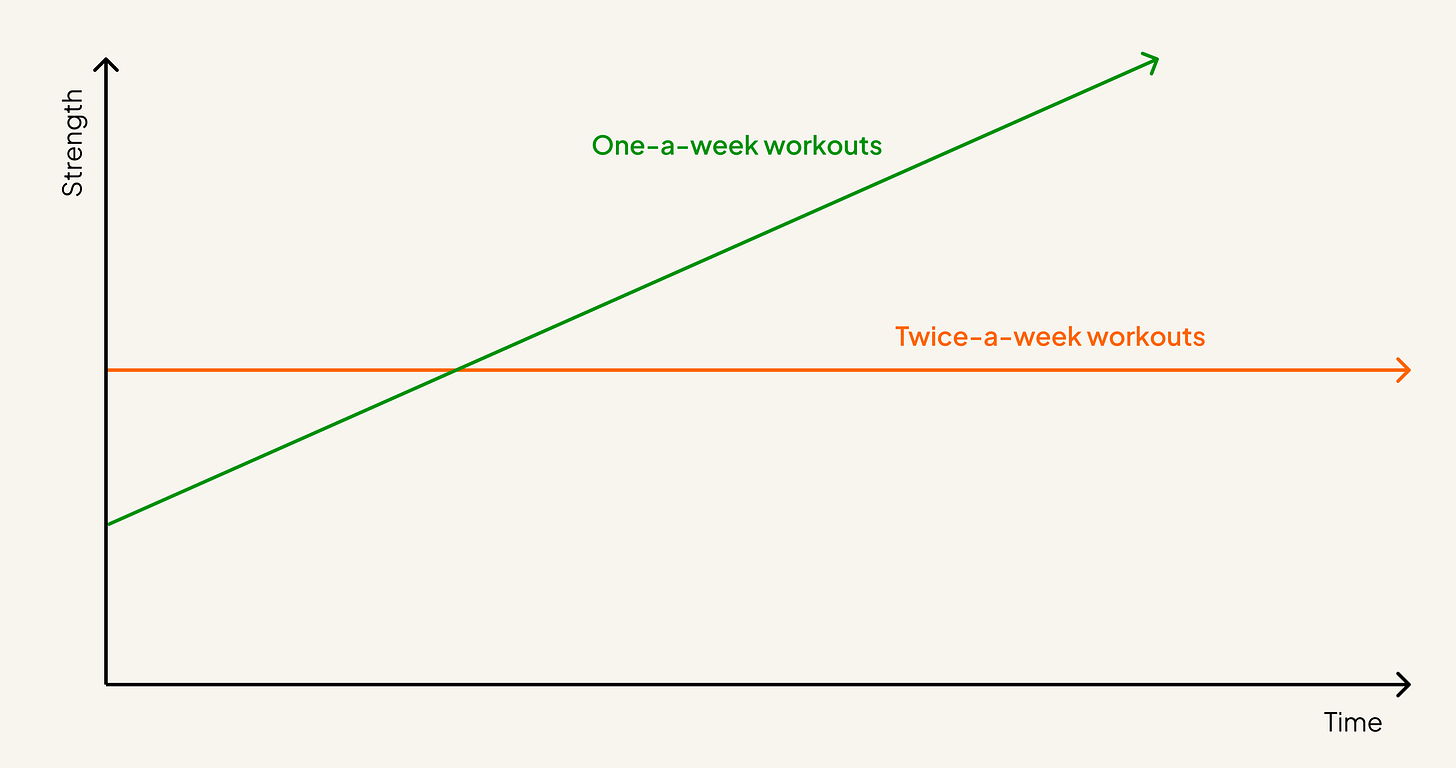

Having said that, now we know balancing intensity and recovery is key to promoting health, below is a counterintuitive yet interesting chart illustrating how reducing the volume of high-intensity workouts relative to a given recovery period could significantly strengthen muscles to their peak — compared to a higher volume with the same intensity and recovery, where the strength progression would plateau. Fascinating!

Funny enough, having trained as a CrossFit athlete for almost a decade now, I’ve only recently started to train less and focus on longer resting windows, feeding my appetite for activities by adding dedicated mobility, stretching and yin-yoga days to help my muscles and fascias recover in that process.

Why should you consider high-intensity?

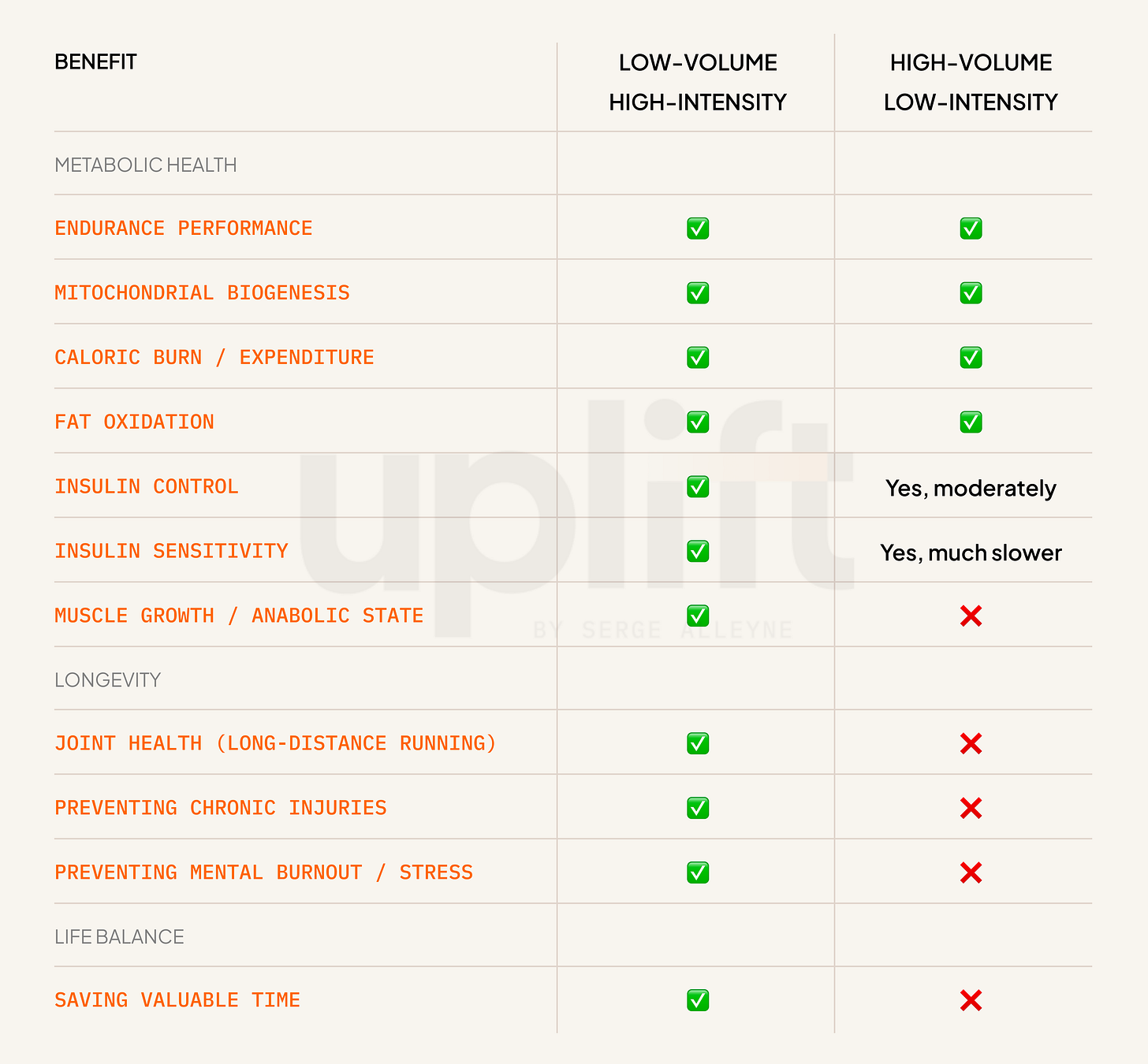

We talked about misleading links between fitness and health, and how prolonged high-volume low-intensity running could be detrimental for longevity; but it’s also important to grasp the multi-facet benefits of low-volume high-intensity running exercises as an alternative. For instance, 4-6 sessions of 30-second all-out sprints with 4 min recovery between repeats, 3 days per week, produced similar muscle adaptations and endurance performance improvements as endurance training that required 5x more time commitment.

IMO, in a world where we’re all chasing time and where time is money, spending time with time-consuming high-volume risky exercises doesn’t make any sense, while other much safer and proper methods could be implemented in our daily lives.

Below is a summary of the benefits compared between low-volume high-intensity and high-volume low-intensity training to help you confront your view on this.

Happy high-intensity workouts 🔥

Take care.

Serge

Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: a systematic review, van R. N. Gent et al. (2007)

What are the Main Running-Related Musculoskeletal Injuries?, Alexandre Dias Lopes et al. (2012)

Impact and Overuse Injuries in Runners, Alan Hreljac (2004)

Predictors of Running-Related Injuries Among 930 Novice Runners: A 1-Year Prospective Follow-up Study, Rasmus Oestergaard Nielsen et al. (2013)

Incidence and Severity of Injury Following Aerobic Training Program Emphasizing Running, Racewalking, or Step Aerobics, by W. Byrnes, P. Mccullagh, A. Dickinson, J. Noble (1993)

Similar metabolic adaptations during exercise after low volume sprint interval and traditional endurance training in humans, Kirsten A. Burgomaster et al. (2008)

Low testosterone in male endurance-trained distance runners: impact of years in training, Anthony C Hackney et al. (2018)

The impact of an ultramarathon on hormonal and biochemical parameters in men, Brian R Kupchak et al. (2014)

Effect of glycogen availability on human skeletal muscle protein turnover during exercise and recovery, Krista R. Howarth et al. (2010)

Changes in Cytokines Concentration Following Long-Distance Running: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Micael Deivison de Jesus Alves et al. (2022)

Muscle damage is linked to cytokine changes following a 160-km race, David C Nieman et al. (2005)